Violence and the Labor Struggle in Industrializing America: the 1910 LA Times Bombing

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries American labor fought a sustained battle against American capitalists over who should determine the wages, hours, and working conditions in America’s booming factories—ownership or the workers. Battle tactics included dueling messaging in friendly publications, lobbying for favorable laws, and confrontations between strikes and strikebreakers. As is well-known, the struggle grew intense and violent during labor protests like the 1886 rally at Haymarket Square and the 1892 Homestead Strike. Less well known is labor activists’ occasional resort to sabotage of anti-union business establishments. In 1910, the Los Angeles Times, a strident anti-union voice in a staunch anti-union state, was a target of domestic violence that took the lives of 21 of its employees.

Why the LA Times Was Targeted

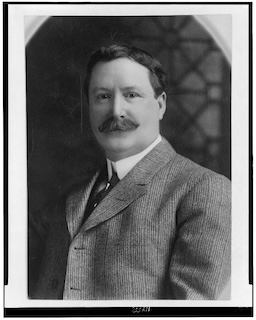

During a highly successful career, the newspaper’s owner, Harrison Gray Otis, had become the political enemy of all unions and a symbol of capitalistic intransigence to worker rights. A delegate to the 1860 Republican Convention, Otis served with distinction in the Civil War, rising to the rank of brevet lieutenant colonel. Following the conflict, he moved to Los Angeles, seeking his fortune in the newspaper business. He landed a job, making $15 a month with the LA Times, but soon saved enough money to purchase the struggling paper with a partner’s help. Otis was not a man willing to share power. He bought out his partner and instituted dictatorial control of the Times. Otis and LA’s other printers were virulently anti-union. Along with other merchants, they organized the Merchants and Manufacturers Association to ensure they remained “masters of our own business.” Members promised not to hire union members, to use lockouts and blacklists to break the unions, and to provide financial support for their fellow members if their workers struck.

When the typographical worker’s union struck LA’s printers in 1890 in protest of wage cuts, Otis joined the other LA papers to break the back of the union. His fellow printers caved, but not Otis. When the union abandoned the fight in 1895, the LA Times became the only non-union shop in the LA newspaper business. Otis became a symbol of anti-union capitalists unwilling to negotiate wages or working conditions.

The Times Owner’s Swift Response

In the early morning hours of October 1, 1910, a bomb destroyed the LA Times building, killing 21 workers and injuring many others. While the destroyed plant still smoldered and authorities searched for survivors and clues to what happened, Otis persuaded another printer to run an abbreviated edition of the Times with headlines proclaiming Union Bombs Wreck the Times. Police discovered an unexploded bomb at his residence the same day, which cemented Otis’s view that unions were attacking him and his business in retaliation for his firm stance against their cause. To Otis, being a union member was synonymous with being an anarchist or socialist; all were radicals bent on destroying property rights and the American system of government. One month before the attack on the Times, an unexploded bomb was found at the Alexandra Hotel Annex in downtown LA, and on Christmas Day, a local non-union iron works plant suffered a bombing. Otis was convinced these bombs signaled a dangerous new phase in a radical campaign to destroy capitalism. He pledged to fight back hard.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation did not exist in 1910, so Otis and the Merchants and Manufacturers Association turned to the most famous private investigator in the United States, William Burns, to find the culprits. Burns believed the case was the most important of his career. If he could identify the bombers and prove the case against them in a court of law, he would not only cement his reputation as the nation’s best investigator but also make himself rich. Burns spared no expense traveling the country in search of clues. His break came when he linked a bombing in Illinois to the attacks in LA.

The Arrest and Trial of the Suspects

Bombers often use consistent methods and materials in creating their devices. Having learned to build a bomb successfully, they repeat the process, sticking with what worked before. Burns and his agents were already investigating a bomb attack on a railroad yard in Peoria, Illinois, when the MMA hired them to investigate the LA attacks. Burns and his agents identified the materials and bomb-making methods used in the Peoria bomb closely resembled those used in the deadly bomb that destroyed the LA Times building. They traced the purchase of materials used in the bomb, and that trail led them to the brother and known associates of John McNamara, the Secretary-Treasurer of the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers. One of McNamara’s hired men, a man named Ortie McManigal, was arrested and confessed to planting several bombs.

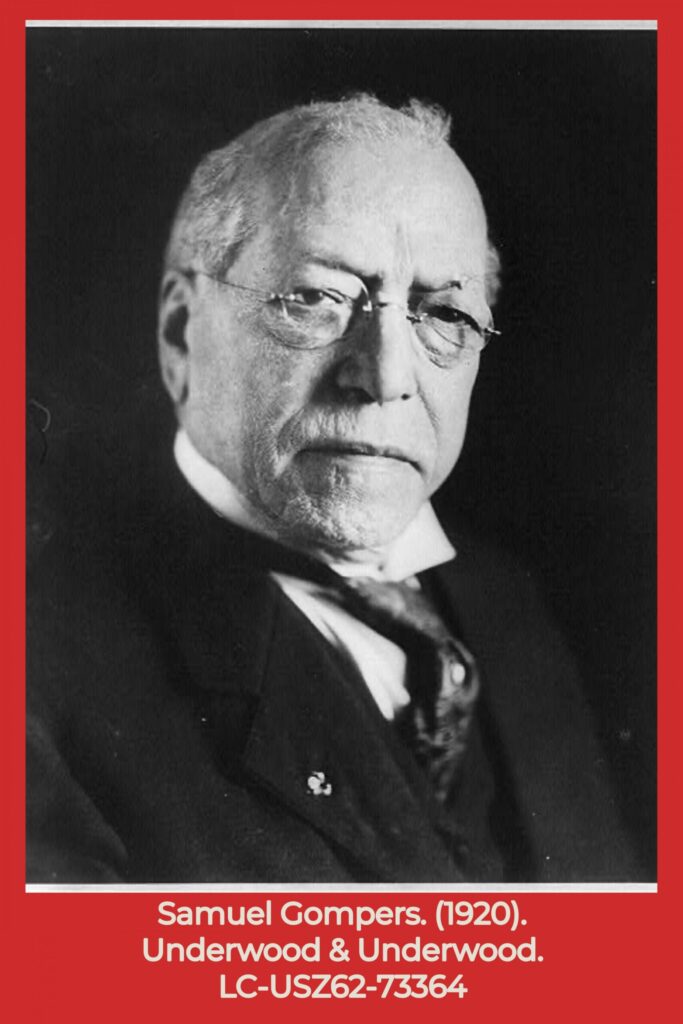

The arrest of union members in connection with the LA bombing enraged union leaders and their supporters. Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor and “Big Bill” of the Industrial Workers of the World was convinced that Otis hired Bill Burns to plant evidence implicating union leaders. He fought back by hiring the nation’s best-known defense attorney, Clarence Darrow. Darrow quickly learned that the evidence Burns had developed proved that McManigal and the McNamara brothers were guilty. A plea bargain agreement was reached, and all three men switched their pleas to guilty and received lengthy prison sentences, shocking Gompers, Haywood, and union members across the country.

Teaching the Complexities of the Labor Struggle

The LA Times bombing is not emphasized in many history classrooms today. Teachers are more likely to teach the Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Homestead Strike of 1892. Why? A domestic terror attack by a labor union is just as disturbing as the Pinkertons’ assault on steel workers in Homestead, PA. One possible answer invokes the old adage, history is written by the winners. The Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 banned yellow-dog contracts in which workers promised not to join a union and restricted the use of injunctions blocking strikes, picketing, and boycotts. The law boosted the strength of unions and helped lead to high union membership in the 50s and 60s. In the 1960s, most Americans would not have associated union membership with incidents of domestic terrorism.

Another possibility is historical awareness of the imbalance of power between unions and industrialists of the late 19th and early 20th century. Industrial owners held the stronger hand. When they were unable to impose their will on workers, they turned to courts and state officials to block activities that they believed threatened violence. Employers had a powerful argument. Domestic peace and prosperity depend on a stable workforce. And violence threatened entire communities. Perhaps American history students should learn about the LA Times bombing so they understand the complexities of the labor struggle in this era.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters Program in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.