‘Hurting because we followed the rules’

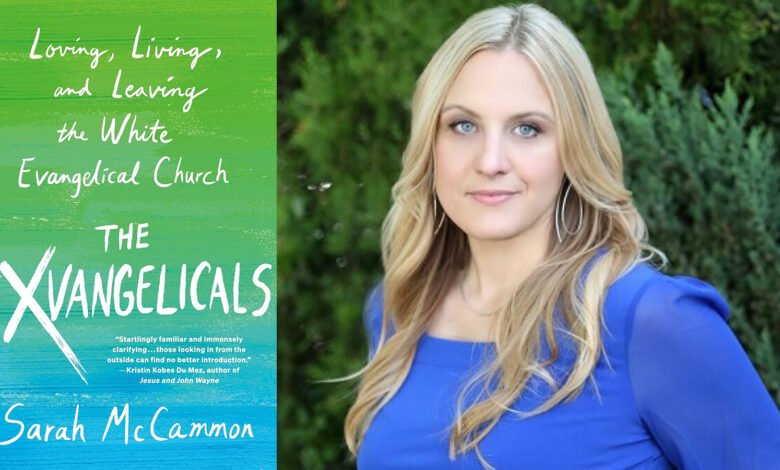

(Sightings) — Calling a book “timely” feels like a backhanded compliment. It seems to suggest that the book’s greatest strength is its publication date. So let me be clear: Sarah McCammon’s “The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church” is both timely and superb.

Timely, because it deals with the issues that will decide the 2024 elections — issues of religious power and bodily autonomy. Superb, because it discusses those issues with sensitivity, sophistication and no small amount of bravery.

McCammon was born and raised in America’s conservative Protestant subculture; she is now a correspondent for National Public Radio, an outlet her father once scorned as “National Perverted Radio.” “The Exvangelicals” is the story of her journey between these two points. And it’s the story of others who made similar journeys; McCammon intersperses her account with quotes from people in various stages of deconstructing their evangelicalism.

“The Exvangelicals” will inevitably be compared to Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation.” That, too, was a timely book. Appearing just a few months before the 2020 elections, it argued that Donald Trump appealed to white evangelicals because his crude, misogynistic swagger embodied the sort of “manhood” preached by generations of evangelical leaders. “Real men” should be tough, aggressive, even violent. And if they happen to sexually assault someone now and then … well, we’re all sinners. (“The Exvangelicals” quotes James Dobson, founder of the evangelical media empire Focus on the Family, defending Trump’s conduct by saying: “He’s not a perfect man, but I’m not either.”)

“Jesus and John Wayne,” as its title suggests, is primarily about men, and in particular men with authority. It’s about the preachers, pedagogues and politicians who defined “biblical” manhood and womanhood. By contrast, McCammon is concerned with those on the receiving end of these edicts, the people who had to live out these visions of manhood and womanhood.

Living “biblically” took a horrible toll on many people. The exvangelicals McCammon profiles (herself included) retain some fond memories of their upbringing, but the book’s dominant tone is a combination of shame, regret and anger. McCammon recalls being tormented by the fear that she might not be among the elect: “If you’d accepted Jesus into your heart, that was supposed to settle it, I thought. But had I really believed, and believed enough? What if I was among the lost?”

At one point, when she was 12 years old, McCammon’s fear of damnation became so strong that she grabbed a knife and threatened to kill herself. Her parents responded by beating her — exactly as recommended by evangelical parenting experts like James Dobson.

These feelings of guilt and shame were particularly acute when it came to sex. Young women in the evangelical subculture were given responsibility without freedom; they were to dress modestly and behave demurely, because to do otherwise would tempt men into the sin of lust.

Unsurprisingly, this sexual ethic rarely yielded healthy relationships. McCammon’s rushed first marriage ended in divorce; when she turned to her family for support, they accused her of apostasy and warned her she might be going to hell. Her ex-husband, also raised in the evangelical subculture, bitterly remarked: “We’re not hurting because we broke the rules. We’re hurting because we followed the rules.”

Lucid as this book is, there is something of a veil over the question at its heart: Why do people walk away from evangelicalism? McCammon does not pinpoint any one moment when she went from evangelical to exvangelical. One thing seems clear, though: Becoming an exvangelical is as much an emotional process as an intellectual one. And the dominant emotion in that process seems to be disgust — disgust with cruelty, lies, hypocrisy.

I’m reminded of how the great Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz described his break with communist orthodoxy: “My own decision proceeded, not from the functioning of the reasoning mind, but from a revolt of the stomach. A man may persuade himself, by the most logical reasoning, that he will greatly benefit his health by swallowing live frogs; and, thus rationally convinced, he may swallow a first frog, then the second; but at the third his stomach will revolt.” The exvangelicals simply couldn’t swallow any more frogs.

I closed “The Exvangelicals” wondering if we are now witnesses to the end of evangelicalism. I’m not suggesting white conservative Protestants will vanish any time soon. They are doing just fine — their numbers, money and organization guarantee they will remain a powerful force in American life for decades. Rather, I wonder if the identity of “evangelical,” promoted by figures such as Billy Graham and institutions like Christianity Today as a kinder, gentler alternative to “fundamentalist,” is fading.

Labels are created to serve a purpose, and the label of evangelical no longer seems to serve anyone’s purpose. It did, once. Those who embraced the term did so in the belief that it could unite conservative Protestants into a nationwide movement for religious revival. Now, however, the label has become so entangled with right-wing politics that those on both the left and the right have begun to avoid it, seeing it as a stumbling block to their religious aims. This is, ironically, the same reason evangelicals like Billy Graham sought to avoid the term “fundamentalist.”

The last act of evangelical identity may be played out within the shell of exvangelicalism. The exvangelicals are, as McCammon’s book makes clear, a diverse group, but they are drawn together by a common foe: a faith they see as complicit with bigotry and corrupted by power. Once, the term “evangelical” united a faith tradition. Now, it unites people who have been scarred by that faith.

(William Schultz is an assistant professor of American religions at the University of Chicago Divinity School. This commentary originally appeared in Sightings, a publication of the Martin Marty Center for the Public Understanding of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)

Source link