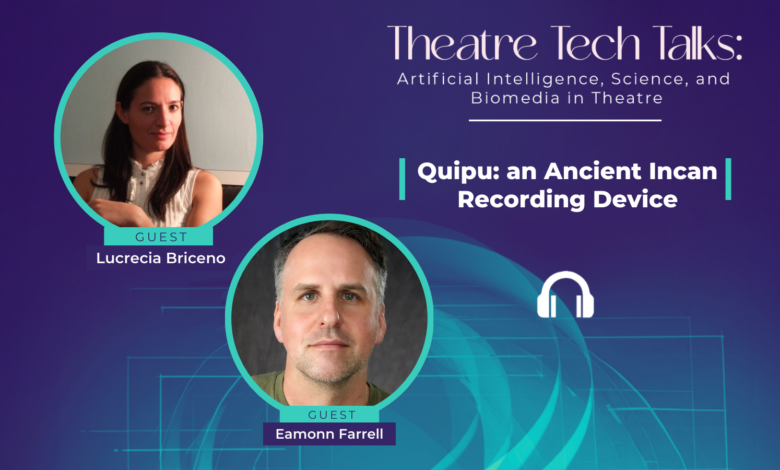

Quipu: an Ancient Incan Recording Device

Tjaša Ferme: Today I had the privilege to talk to Eamonn Farrell and Lucrecia Briceno of the Anonymous Ensemble, a devised company based in Brooklyn. We talked about their theatre show called Llontop, a technologically ambitious installation and multilingual performance that centers on Quechua voices. They connected the technological and modern with the exploration or demystification or maybe mystification of the ancient.

Welcome to Theatre Tech Talk: AI, Science and Biomedia in Theatre, a podcast produced by HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. Hi Lucrecia. Thank you so much for joining us.

Lucrecia Briceno: Thank you for having us.

Tjaša: Welcome Eamonn. Thanks for joining us from Jersey this morning. Lucrecia Briceno is a Peruvian artist currently based in Brooklyn. Much of her work has been in association with artists developing innovative and original pieces. Her work includes theatre, opera, puppetry and dance, as well as collaborations in several non-performance projects. Eamonn Farrell is a Virginia-based theatremaker and video designer. With his Brooklyn-based theatre company, Anonymous Ensemble, he has created dozens of original media-infused shows, installations, and live webcasts in New York City and around the world. Llontop is a technologically ambitious installation and multilingual performance that centers on Quechua voices. Can you first tell us who are Quechua and what really inspired you to embark on this journey of creating this show?

Lucrecia: Well, let me just start with the second part of the question. So, I’m originally from Peru. I was born, raised, educated in Peru, and arrived to United States in 2004. And Eamonn happens to be one eighth Peruvian, is that correct? Quarter Peruvian, I’m sorry. I always forget how much Peruvian you are. So he and I, we have been working as designers for a very long time. I joined Anonymous Ensemble, that was a theatre company that was founded by Eamonn and some other folks that are still part of the company, some that they’re not.

But we spoke a lot about Peru and being raised in Peru and Eamonn, I think was very curious. So from these conversations, we sort of decided to embark ourselves in a project that was, well, at the moment, we weren’t sure what it was about, but that it was based in Peruvian culture. And really quickly, through a lot of research and research and more research, we came to what we’re doing now. That is a multi-technology, multilinguistic sort of experience. So, we will not call it, this is an installation or a show, it’s more than that. It’s blending different type of medias and different type of genres into a performance. So, I don’t know if Eamonn wants to add anything to that.

Eamonn Farrell: Well, so one of the very beginning of the project was really me and Lucrecia having a conversation in a kitchen in Idaho where we were both designing a show, and Lucrecia had been to a Peruvian restaurant there that day and had mentioned that there’s a lot of indigenous Peruvian people in this very wealthy town of Sun Valley, Idaho who were brought there to raise sheep in the mountains because they were very good shepherds. And that led to a conversation about indigeneity and ancestry. And I mentioned that I had always been told that I was one-sixteenth Incan indigenous. And Lucrecia kind of laughed at me and she was like, “We’re all indigenous, but nobody admits it.”

And that began this conversation about indigeneity in Peru versus North America and how in North America, everybody wants to have that sort of claim to the land or something, some sort of long-lost indigenous ancestor. Whereas in Peru, which is a majority indigenous country where the majority people do have indigenous ancestry, people are much less likely to admit it publicly. And that was news to me. My grandmother had always said that she was a hundred percent European, but I didn’t realize that that was kind of a cultural value there and that there was such a stigma associated with indigenous ancestry.

So, as we began researching the project, well, Lucrecia first told me a lot about it, and then we started to talk to Quechua scholars and artists, and it became very clear to us that the piece needed to be about Andean indigeneity and that we needed to work with actual Quechua artists. And so then we had this meeting with this poet, this Quechua poet, Irma Álvarez Ccoscco, and it became clear that her voice really needed to be the voice of the piece. And it is. Her writing, her poetry, and her performance are really at the center of the work.

And really, it’s about what we’ve learned from her about Quechua culture and also from her community, many others that we’ve interviewed about Quechua culture, Quechua language, the history of the people. And it’s very important that it’s a history that is from an indigenous perspective, because I had read lots of… I’ve always been kind of, what would be the word, like a Peruviophile. I’ve always been really curious about it ever since I was a kid and read a lot and listened to music and tried to learn how to do the weaving, all this stuff. But came to realize that really I was getting everything from a colonialist perspective. Even the history, the story of Pizarro conquering the Incas has this sort of patina of colonialism. And so, getting that history again, and the piece is really a history. The poems span from the 1500s to the present day. Getting that history and presenting that history from an indigenous perspective is a totally different thing. It’s a different understanding of time and oppression and survival. And—

Lucrecia: And I would just, going to add, for me, for example, just speaking about this and trying to articulate emotions and things like that are very hard. So I’m so glad that Eamonn is sort of putting in that perspective and framing it the way he does, because he does such a better job than I do, because I’m emotionally tangled into it. Because even though I am Peruvian, but I didn’t, was brought up in a indigenous culture, so it’s a different thing. So my prism is also very different. So, I have had my foot in one community and been sort of allowed to participate in the other. It’s a tricky way to manage that.

So really, meeting Irma was amazing. It was just really, it free us to just really went in through her eyes and the history of indigenous people, in particular from the area of Peru that she’s from. So I think, and within, we were able to reach out to different communities in New York City, in Virginia, in Ohio, we were able to expand our center of community. What does it mean to be a Quechua community in the diaspora, or in Peru? So it was just a lot of that. The project keeps changing because of community.

Eamonn: That was a very long answer, and I don’t think we actually answered what is Quechua. And so, Quechua is a language. It is the language of the Runasimi, which basically means the people in the language. And it is a very interesting indigenous language in that similar to Latin, the Quechua was the language of the Incan Empire, which spanned all the way from Ecuador to Bolivia. If you turned the Incan Empire on its side, it would span from New York to San Francisco. It was a huge swath of South America, very similar to the expanse of the Roman Empire.

And similar to the Roman Empire, when the Incan Empire was conquered or invaded, which is a better term for it, the language sort of fractured into a whole bunch of different dialects that run all the way from Ecuador to Bolivia. But the wonderful thing is that Bolivian people can communicate with Ecuadorian people in that language, especially in the mountain communities. And so, it’s really like a family of languages. You could almost say it’s like the romance languages. Quechua, it ranges from Ecuadorian Kichwa to Bolivian Kichwa through all the dialects of Quechua within Peru and throughout the Andes Mountains.

Tjaša: Fantastic. So, what would you say that the actual population that still actively speaks Quechua or its dialects is?

Eamonn: It is the most widely spoken American Indigenous language, and it’s spoken by about eleven million people today, which is substantial.

Tjaša: Wow.

Eamonn: I mean, it’s a very much alive language. There’s movies in it, there’s obviously poetry, novels-

Lucrecia: Music, yeah.

Eamonn: … A lot of young rap artists are singing in Quechua and rapping in Quechua. So, it’s having this burgeoning of pride right now, which is really exciting.

Lucrecia: Yeah. That is very new. This is a very new thing. This is a generational sort of thing that is bringing Quechua in the forefront. That people are not ashamed of studying it and reading it and using it, when it used to be a stigma in the seventies, eighties, and early nineties. I think way into the nineties, it was not considered appropriate really. So that was a terrible thing. But no, as Eamonn mentioned it, now it’s expanding and we are very thrilled by that. The new generations actually learning the language and artistically expressing themself in that. So that feels there, it’s a live language that keeps changing too. So it makes it so-

Tjaša: That’s really hopeful.

Lucrecia: … Yeah, it’s really interesting. Yeah.

Tjaša: I love this comeback of the indigenous cultures and sort of centering ourselves in who we are, not who the popular culture, the global culture is trying to make us, which I feel like is just such a trend everywhere. First of all, what I love about this is that you’re finding ways to work with technology to bring something ancient back to life. That is very much also alive right now. But the next little thing that you do is, you include the glowing Quipus sculptures that emit light into the installation. And Peruvian Quipus are an ancient Quechua devices for recording information. This blew my mind when I read it. What do you know about Quipus? How did you learn about them? Tell me everything.

The potato as we know it is part of technology.

Lucrecia: Well, we could refer you to Manuel Medrano, Dr. Manuel Medrano. He’s an amazing scholar that spoke to us, and he wrote a book about it. But I think in our interview to him, it was incredibly an eye-opener and sort of a… Because Quipus has been described as many, many different things through many generations. But the way that he describes it, I think is the most appropriate for us at this time in which nobody really knows what the Quipus are really seen in this magnitude, because Quipus are objects that they have been found in archeological sites and they have been seen in paintings. And that’s how we know that there’s a link of these objects to the Incan Empire. But the way that he described it, it’s like an Excel sheet, in which you could, we don’t really know. We know that there’s a count for them, that you could count dates and you could count amounts, but within those Quipus, you could also have different colors in one string of knots. The Quipus are really knots.

So with that, it’s like an Excel. You don’t know what you’re counting, you don’t know what you are putting in a spreadsheet. And there’s large spreadsheets that people know, it could be familial histories, it could be storytelling, it could be just accounting. The most known that we know about them, they’re accounting. But just going to the beginning, beginning of your description of the piece, one of the things that in one of our research when we were talking and we were reading and speaking to each other and speaking with other folks, is just somebody mentioned, and I forgot who it was, that the potato as we know it is part of technology. Potato has been a technological item that has been developed for centuries, and we don’t think of those things like that. So, we were trying to open our minds to what is technology, technology from a human necessity too. So, we were grappling with all of these ideas when we started originally the piece.

And Eamonn and I, because we work together, I mean, he works as a projection designer and I work as a lighting designer. Our idea was to, how light could be a center of our design of images. So, we did all sort of workshops on all sort of things. And one of the things that we were excited, is to borrow from Eamonn’s collection of objects from his family, things that mean to him, they have a relationship with his own history of traveling, of migrating. And we put them in our exhibit, let’s say.

So then we started developing, and Eamonn, thankfully with some great friends of ours that do technology too, Eamonn and them were able to create software in order to put your telephone on an object, and by the way that it’s lit the color of the light that is lit, it will give you information in your headset of something that we curated as a voice of the interviews of all these people. I mean, to create a multimedia, multilingual… we had to talk to a lot of people and a lot of interesting people with so many different backgrounds, so many incredible backgrounds. And we were able to use those voices to bring it back to people that were coming to see these objects.

Tjaša: Oh my God, there’s so much to unpack in everything that you just said. First of all, since this is a podcast and we don’t have a visual and we can’t show videos or imagery, can you describe what a Quipu looks like? What it looks like, what it used to look like, and how did you redesign it with lights and LED neon ropes?

Lucrecia: A Quipu is a long string with knots. And from the main string, different strings come down, they are knotted to the first one. There’s a name for it, that is the main thread. And then all these little threads dangle from them. And usually they have been, the ones that have been found—because again, they have been found in archeological sites—they are a color of wool, just undyed wool. But some Quipus do have color, have reds and different tints of reds and a little bit of yellows, and sometimes the color grades from the top to the bottom. But from this main thread, it could be like fifty smaller threads with different sizes. And each threads that is dangled do have knots to create some information. And again, in this case, when I use them for our performance, we were using this as markers of dates, that they’re important and they’re linked to Irma’s poetry, but they’re also linked to Peruvian history.

We happen to be rehearsing at a friend’s theatre space, it’s more like a large studio in Red Hook. And she happened to have these neon rope lights. So we decided to hang it, and thankfully, it’s one of those spaces that is not a small space, but it’s a large space with a really beautiful vaulted ceilings, so we were able to hang them. And at the beginning I was like, “Is this a creature? Is this a wing at this? And who’s touching it? Who’s doing it?” Because Quipus are, we all in Peru grew up knowing what they are. And it’s part of iconography, like a visual iconography that we see all the time.

Tjaša: Would this traditionally be hung in a house or in a town square?

Eamonn: The Incans actually had a class of people who were sort of scribes, who were quipucamayoc, they were called. And they were the experts, and they could both make Quipus, which is like the Andean equivalent of writing, and read the Quipus. And the really tragic thing is that the Spanish, the conquistadors had no interest in this technology at all. And nobody investigated it or recorded what any of it meant. Nobody sat down with a quipucamayocs and was like, “Tell me what does this knot mean? What does this color mean? If the knot’s here, if it’s tied in this way, what are you saying?”

So what’s really interesting about Manny’s work, he’s the scholar, is that he’s using AI to compare Quipus that exist with historical records to try to unlock what the actual meaning… Because we have thousands of these Quipus, and there’s so much meaning stored in them that we can’t access because the conquistadors didn’t care enough to actually preserve that knowledge. And the really tragic thing is that Quipus were still actively being used until the 1950s and still nobody cared. And so, nobody went to these villages up in the Andes to even talk to those people, those elders in these communities to find out what they meant. And now scientists have to use AI to try to figure out all this information that we have. We have tons of information that we just can’t access. But the one thing that we do know is the numbers. We know what a knot, like five, ten, one, two, three, four, five. So that is the one thing that we use the Quipus in the show to represent, is the numbers of the dates, because—

Lucrecia: The numbers, yeah. But I love how Manny puts it. It’s like you have the library of Alexandria in front of you and you cannot read it.

Eamonn: … She grew up speaking Quechua at home, but really studied it in an academic setting to really learn the grammar, the ins and outs of the suffixes, it’s a very complicated, it has a complex construction, the language. But there are things that are in Quechua that are cultural phenomenon that we just don’t have. And by learning the language and by learning specific words, even Westerners, and Irma will talk about that. She’ll talk about how Quechua culture and language has a lot to teach the world. There are concepts in the culture and in the language that when we learn them, we have access to a whole hemisphere of—

Tjaša: The wisdom of the people. So it’s kind of locked, it’s built into grammar and cultural notions.

Eamonn: … Yeah, and just concepts. She talks about the word mayu, which is river, and has the first song in the piece is called Mayu. And she’ll talk about how river is not exactly the correct translation for it, because within the word mayu, there’s also clean, like clean water. And so, you wouldn’t call a polluted river a mayu in Quechua culture. And that has to do with a value system where humans have an obligation to Pachamama—to the earth, that is built into our conception, like how we think about it. We can’t call it a river if it’s a polluted river because we’ve fucked it up and turned it into something that it’s not. And there’s a lot of concepts like that that we’ve been learning that come from this culture, that still exists in this culture and that we can still access if we take the time to learn about it and to really delve into it and to talk to these people and talk to the elders. And I think that that’s a really beautiful thing about the project.

Tjaša: Thank you so much for bringing these objects and concepts and questions into this performance. The idea of Quipus, an ancient document and ancient information system builder, that really excites me, and I love that you’re using technology and everything that’s available to us now to talk about it and propel the interest and curiosity into what this culture has to teach us. Can you speak a little bit about, you said that you talked to a ton of people and that you recorded a ton of interviews. And that you then build them around these objects, pre-Columbian objects that are also connected to your family heritage, Eamonn. You said, Lucrecia, you said that you basically, depending on the position and on the light that was hitting the phone, that’s really what unlocked a particular story. Can you talk a little bit more about this?

Lucrecia: Let’s just explain about the installation first. I mean, explain what installation is. I mean, Eamonn found this drawing of this particular architectural sort of form that is used in Inca culture. And based on that shape, we sort of created these pedestals. And these pedestals, we added these objects on them. And in the top of the pedestal, just sort of will be the highest part of the exhibit, we put a down light. We got this amazing grant, and we were able to buy these LED parts. We needed something that it was bright enough, strong enough, but also light enough and not expensive, of course, because we needed sixteen of them.

So we hang them over there. And then all these pedestals, these pillars are in a round shape in a way. These square pedestals are created in a round shape. And Eamonn created these amazing, beautiful woven skirts for each one of them. And then underneath, we also put a different light to sort of contrast what the top light is doing. So it’s really a design thing, but it’s just adding more shapes and more… We layered the installation even more with time. But so the light being on the top, it sort of hits the object and we put a small little square mirror to hold the object, and then it sort of makes the object really glow. So, we have different objects in sixteen of these pedestals/pillars, and we light them in different type of colors.

Eamonn: The colors have both an aesthetic function, obviously, and then also a sort of practical function because we’re basically using Google’s Teachable Machine, which is a free web-based interface that they’ve offered that anyone, you can go to the Teachable Machine and train models based on images. So, we use Google’s Teachable Machine to create machine-learned models for different views of the objects. And so the color really helps to distinguish the objects from each other.

And then, we’ve worked with a very wonderful group of software developers who are our company angels to create the actual interface between the models that we create, the machine-learned models, and our media software, which actually functions in the cloud because we need so much processing to handle all of that machine-learning recognition. So basically each audience member has a cloud machine that is running our suite of software that results in hopefully the very simple experience for the audience of going around the objects and with our phones, framing them in certain ways, and sort of searching for a specific frame that the machine has learned that will then trigger a specific piece of audio that relates to what they’re looking at, but also relates to where they are spatially and the kind of narrative, choose your own world that we’re creating for our audience.

Tjaša: That’s amazing. What’s the company that you worked with, the amazing angel company that created an interface for you?

Eamonn: Well, the company is Zoom, but a former student of mine works with previous projects of ours, developed software when he was still a student of mine. He’s a brilliant artist and technologist and coder, and he created a version of Zoom for a pandemic project of ours that then got used by theatres all over the world and then got bought by Zoom. So now he works for Zoom. And he’s the one who coded the software that allows us… Because it’s all Zoom based. The audience is just using Zoom, the camera that they’re using, and the sound is coming through Zoom, but sort of not allowed to say that—

Tjaša: That’s okay.

Eamonn: … officially supported by Zoom. But it is within.

Tjaša: I mean, it sounds incredible. It’s great to have resources and incredible geniuses like that at a reach of a grasp.

Lucrecia: We started also as a company, we also come to terms with the idea that all the materials or things that we use, they need to be something that is accessible for the people that are coming to see our show. So just using a telephone for example, for me was incredibly important. So that the final little bit of the technology we needed to use is just one of the things everybody… I don’t want to say everybody, but almost everybody in the world will have a smartphone because it’s a lifeline to knowledge, to people, to family, to everything in the world. You are a refugee in a refugee camp or you are herding your sheep in a mountain, you have your telephone to just connect. So that was important for us.

Tjaša: I love that. I guess I’m also interested in, so the space around the object was almost like a grid or it was coded like a grid. And I’m just curious how many different points were there that were active with different audio files?

Eamonn: It’s very computery, it’s sixty-four. So there’s sixteen pedestals, there’s sixteen objects and there’s four views for each. So there’s sixty-four loci or sixty-four… The model is a sixty-four class model that we use. But the form of it itself is a Chakana, which is sometimes called the Andean cross. And it’s a very ancient Andean symbol that it’s basically like a circle inscribed in a square with these sort of cross-like overlay. And that is an interesting story because I use that as the model. I just ran across it on the internet and I was like, “Oh, this is the form of the piece.” But then it was explained to me later by an elder, a Quechua elder in the community why we use the Chakana. And that is that it’s also stairs. It’s so hard to explain. It’s like a four-dimensional Escher-esque set of stairs that are bridges between the different ukhu pacha, which is below earth, but it’s also, has to do with life and death and ideas of past and future.

So, it’s a form that’s bridging all of these different phenomena. That’s a very easy thing for an Andean person to understand, and something that was very difficult for us to wrap our heads around. And within that concept, that world view, the distinctions between past and future are not so linear, and the distinctions between life and death are not that linear.

Lucrecia: Ukhu pacha is the underworld, kay pacha is the preserved, it’s what is the world that we perceive and hanan pacha is the sky and the moon and all this stuff. So, we have it on record, then we get it right.

Tjaša: Fantastic. Now we got it right. Okay, great. I’m saying that maybe we can delve into our last question, which is a little bit more philosophical and a little bit more personal. Which is, what does technology mean to you? What can you, what would you like to achieve with technology? How do you use technology? Is it a tool, is it a partner?

She’s not going to be satisfied until indigenous languages have equal footing on all technological platforms where they’re offered and supported.

Eamonn: I mean, I think ultimately it’s a tool. It’s interesting talking to Irma about technology, because her interest in the project was really very much rooted in the technology associated with it. She’s always been an advocate of the use of technology in indigenous languages and culture. That’s been a huge part of her advocacy throughout her career. And when we started the project, Google did not translate Quechua, which made things very difficult for us. But because we use Google Translate in a lot of our intercultural work with spreadsheets and everything, and we use it just automatically.

And when Google Translate finally added Quechua as a translated language in the midst of the project, this is last summer, the New York Times interviewed Irma and another person who was part of our project, and they were like, “So what do you think now that Google finally translates this language that’s spoken by eleven million people that it should have translated ten years ago?” And Irma, her response was, “I want more.” She was like, “Yeah, good, but I want more.” She’s not going to be satisfied until indigenous languages have equal footing on all technological platforms where they’re offered and supported. So, all this to say that technology is a means of empowerment, and it is also, can be a tool of oppression, and it’s a way of establishing power dynamics, I think. And I think it is something that we should pay a lot more attention to: who has access to technology, who’s getting trained in it, and what are the possibilities for equity in how technology is applied.

Tjaša: I love it. That’s a great takeaway.

Lucrecia: That’s great. That’s great. I was going to say… I was going to tell you my experience last night, I was to my husband, he’s like, “I’m going to walk the dog.” And I said, “Get off the phone. Too much technology, can we go back to the time in which we didn’t have phones so we could actually spend time?” But I think that you’re being more reflective Eamonn, I was just going through my daily routine of what I need and what…

Tjaša: I mean, that’s legit. That’s legit. It’s another point of view, for sure.

Lucrecia: No, it is. It is. But also as a designer, because being part of Anonymous Ensemble, it has become a big, big part of my work. But I also do work as a freelance designer. So technology for lighting designers is opens a different vocabulary. And before we didn’t have neon, LED fixtures, and now we do, and they’re changed. Somebody told me one time, when you buy one piece of technology, you know that, I’m not really sure how much was the time lapse, but it was just like, let’s say a month later what you bought was four generations behind already. There was something of that. So knowing that we keep buying, doing more LED and we’re consuming technology in a way that sometimes is a little scary.

Sometimes a designer, I demand the technology, I need it, I must have it because all the cool kids have it. But also sort of reflects a little bit of how you’re using the technology. And at least for a designer, technology is just a tool for language, for communication, whatever type of communication it is, verbal, un-verbal, visual. It is funny because Eamonn and I, we work with visual work, so we are visual dramaturgs. That’s how we always call myself. I’m not just a lighting designer, I’m a visual dramaturg and I want the teams that work with us just to acknowledge that in the sense that light is a language and it’s as sophisticated as many things, as poetry is. Yeah.

Tjaša: Thank you for that. What’s the next thing that the audiences can come to? Where can we see you? Where can we learn more about you? Website, Instagram. What’s cooking?

Eamonn: It’s all Anonymous Ensemble. So it’s @anonymous_ensemble, I think is our Instagram. Website, anonymousensemble.org. And our next project that we’re, our big sort of multi-year thing that we’re developing is a piece called Body of Land that is about it… It’s funny, coming out of this project that was very much about indigenous culture, the inception of Body of Land owes a lot to that, a different understanding of land and particularly land ownership and land usage. And so—

Tjaša: Land is technology, like a potato.

Eamonn: Yeah, I mean, and its power and who has control of it is really important. So we’re partnering with Greenspaces. So we just wrapped up sort of a spring, summer, fall residency at the Westbrook Memorial Garden in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, where we really delved into the history of the land and also the community associated with it and interviewed people, talked to people, longtime residents, new residents, gardeners. And we ended up becoming really interested in the plants. And so, the plant’s perspective and ideas of land ownership from a plant’s perspective. And so, we developed a sort of technological play where the plants are actually speaking and we’re using Lucrecia’s lighting and my projection to bring the plants to life. And then we’re using the voices of the community. So the community’s actually voicing all of the plants, which is an incredibly lovely process to work with these community members.

Lucrecia: And we do it with people in Brooklyn, but our goal will be how gardens in, let’s say Santa Fe, are different from here, and what do those plants have to say about the environment and community relationships and all that stuff. So, it would be amazing to be able to explore all of the things. So, it’s quite ambitious in the spectrum.

Tjaša: So much fun. So you have people animating voices of plants? But then also are they writing what the plant is saying or is this somewhat provided to them?

Eamonn: We created a script that we actually then filter through AI, through ChatGPT filters to create this sort of plant speak. And then we just record the parts with community members. We sort of work with them to cast it but we’ve got, we’re very focused on the pollinator garden, so we’ve got Sedum, we’ve got Aster, we’ve got Sunflower. What do you feel like you most identify with? And then we work with them to create the role that they play.

Tjaša: This podcast is produced as a contribution to HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of this show and other HowlRound shows wherever you find podcasts. If you love this podcast, I sure hope you did, post a rating and write a review on those platforms, this helps other people find us. If you’re looking for more progressive and disruptive content, visit howlround.com.